Olive G. Pettis was the first woman author to register a copyright in 1870, the year that copyright registration was centralized in the Library of Congress. Women who want to commercialize or disseminate their works have always had access to copyright. This is especially important today in the creative economy.

There is a gender gap in IP systems worldwide. Research indicates that women who publish scientific papers are less likely to be researchers than women who write them. The proportion of women who use the patent system is still low relative to the number of scientific papers they publish each yearly. This pattern is sometimes called the “leaky pipe” by some scholars.

Recognizing the severity of this imbalance, the United Nations General Assembly adopted the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development with 193 members states. The Agenda became effective January 1, 2016. It emphasizes the importance of gender equality and empowerment of women, girls and boys in achieving all Sustainable Development Goals and targets.

The World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO), a United Nations specialized agency, is committed to gender equality in the area of intellectual property. It has taken steps to increase the visibility of gender equality and even mainstream it within its day-to-day operations. This includes the breakdown of IP data by gender to provide a key performance indicator for policies that promote innovation and creativity, as well as economic, social and cultural development.

Both the private and public sectors have been working together to evaluate the gender gap in intellectual properties.In 2016, only 12 percent were women. This number rose to 12.8 percent in 2019. Professor Joel Waldfogel is the 2021 Kaminstein Scholar-in-Residence. He has updated portions of Professor Brauneis’ earlier research with new data until 2020. These additional data years provide insight into the current state in gender representation in copyright registration systems.

WIPO’s data about patents and gender show a positive trend. Gender participation in the IP systems is improving. In recent decades, almost all indicators related to gender imbalance in WIPO’s Patent Cooperation Treaty(PCT) and the entire patent system have shown some improvement. Although this is true in many countries, it is not evident in all technical fields or in every company. The increase in PCT applications containing at least one female inventor has been observed in all regions. This is the “country of origin” for patent offices.

Copyright Registration Data

The Copyright Office’s registration data includes over 20,000,000 records, dating back to 1978 through 2020. While the Office doesn’t collect demographic information about registrants, registrations include author’s first names in approximately 13 million records. These 13 million records were the main data used by Professor Waldfogel for his analysis. Statements of authorship (indicating that author is a female) and statements of copyright owner (indicating that author is not necessarily the author) provided key variables. However, 99.8 percent of records were analyzed. These records did not contain any information about the author or the owner claimant.

Inferring Author Gender from Names

First names are often given at birth and can be used to infer gender. Names on copyright records have been assigned to two genders. Initially, first names were matched with names in the World Intellectual Property Organization’s (WIPO) names database. The database contains 173,723 different first names, which can be assigned either male or female. Matches were made to Social Security records to determine if the first names are predominately male or female for names in the copyright database that did not match the WIPO data. These two methods resulted in 182,967 first name matches, which accounts for 96.1 percent copyright records that contain a named author.

WIPO created a global gender-name dictionary that includes 6.2 millions names from 182 countries. This was done in order to identify the gender of inventors and designers. WIPO regularly updates and maintains this dictionary in order to expand the global reach of its IP and gender statistics. Statistics and research on gender and patents are published annually.

Gender Diversity in

Copyright–Related

Creative Occupations

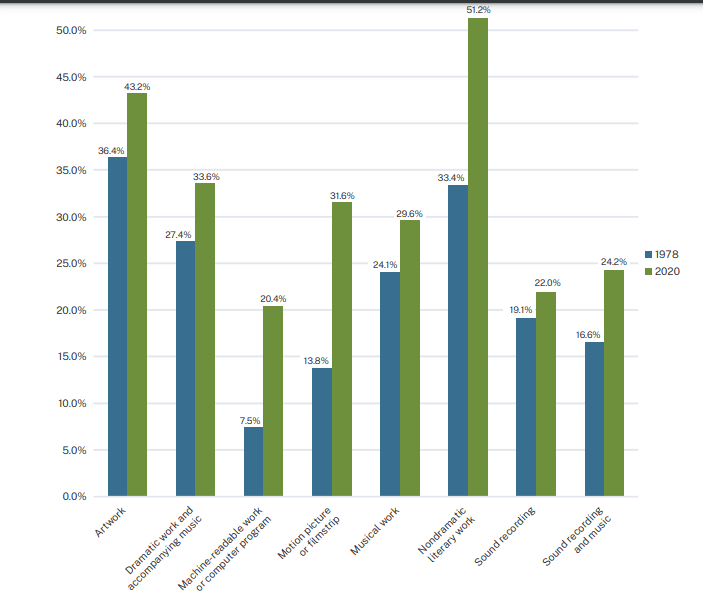

Authors from different categories of registered works have different percentages of women. Women still make up a significant portion of registered works in most categories. Data can be used to evaluate the extent to which women authors are underrepresented when they use the copyright registration system. It may also be used to compare the levels of women’s participation to similar creative occupations. There is some variation in copyright categories due to differences in occupational participation. It is noteworthy that the registration rates of women authors are significantly lower than the corresponding occupational participation. There may be a gender gap in the use and enjoyment of the copyright system.

Comparison of Occupation & Registration Participation Rates.

Literary Works

Literary works examples include; fiction, nonfiction, and poetry. Between 2003-2020, 57.5 percent of self reported writers and authors in BLS occupational data were women. However, only 46 percent of authors listed in nondramatic literary works registrations were female. This means that women authors were about 20 percent less common in the relevant copyright registers over this 18-year period than writers who are occupationally identified.

Performing Arts Music Industry

The registration rates for music-related works written by women authors can differ significantly depending on the proportion of women singers and musicians. Just under 30% of all music-related copyright registrations are made by women. Women authors are listed in only 23.4 percent of sound recording registrations. This compares to an occupational participant rate (34.7%) which means that they are 32.6 percentage less common in registrations than their occupational participation. Women authors in musical works were included in 26.6% of all registrations, compared with an occupational participant rate (34.7%), which means they were 23.3 % less common. Comparing the 2000s with the 2010s, the gap in women’s copyright registrations in both the categories of musical works and sound recordings, and their occupational participation, remained constant. However, the gap in women’s authorship and occupational participation in sound recording and music registrations has decreased from 31.9 percent to 39.9 percent in 2003 to 2010, to 31.9 percent in 2011 to 2020.

Motion Pictures

According to the BLS data women make up nearly 22 percent, 31 percent, and 35 percent respectively of motion picture-related jobs. However, when these rates are averaged over the years 2003-2020, women authors were about 23.5 percent more common among copyright registrations of motion pictures or filmstrips that those in occupations within the film industry. The gap between 2003 and 2010 was 24.9 percent, but it has decreased to 22.5 percent from 2011 to 2020.

Artworks

Between 2003-2020, 51 percent of self reported artists and related workers were women. However, only 42 percent of artwork registrations listed them as authors. Accordingly, women authors were 19.2 percent more common in the relevant copyright registers than those who are artists. This gap has increased from 14.3 percent – 22.5 percent over the past 20 years and warrants further investigation.

Science and Technology

Women account for nearly 27 percent of all employees in STEM fields according to the Census Bureau. Although many professionals create computer programs and other machine-readable works, such as software developers, database administrators, architects, and video game designers,50 computer programmers were chosen to be a reference point because of their close relationship to copyright work. Between 2003 and 2020, approximately 23 percent of computer programmers were women. Women accounted for 18% of computer program registrations or machine-readable works authors during this period. This data is combined with the occupational participation rates of computer programmers shows that women are 22 percent less likely to be listed as authors in machine-readable work or computer program registrations than their counterparts in the related profession. Similar to the differences in registration and occupation participation for other creative categories. However, since 1978, the number of women authors registered in machine-readable works and computer programs registrations has increased substantially. For the period 2011 to 2020, however, the gap between women authors’ registrants and their occupational participation has shrunk to 9.8 percent.

Women Participation in Patenting by Regions

Standard indicators of economic performance such as GDP per head do not account for the gender gap. Brazil, Mexico, and other middle-income countries have a higher gender balance in international patenting than countries with high incomes like Canada, Denmark and Finland. The top-listed origins have the largest gender gaps, with South Africa, Italy, Japan and Italy having the highest.

Participation in patenting by women is not evenly distributed in different countries and regions. It is also not equal in absolute terms. This is why women who patent in Germany, Japan, or the United States will be a major factor in the advancement of gender equality in the coming decades. Patenting in certain technology fields may be more advanced than others. However, they could also be growing at a faster rate than others. In the future, gender balance will be affected by increased patenting in ICT-related technologies and life sciences. Policies that promote gender balance in business, which files the majority of patent applications, may have a greater impact on gender balance than policies implemented in academia.

Gender balance in the patent system will likely be a result of a social process. This involves accumulating imbalances and balances from past institutional settings. Future gender balance will depend on the nature of gender balance evolution in different scientific fields, higher education institutions, and innovative industries.